Archive for the ‘Posts’ Category

About Danny Kucharsky

Danny Kucharsky is a multiple award-winning journalist based in Montreal, Canada who has written for well over 50 magazines and newspapers in Canada and the United States. His credits include The Globe and Mail, Montreal Gazette, Maclean’s, Chicago Tribune, Profit and a wide variety of business, specialized trade and medical magazines.

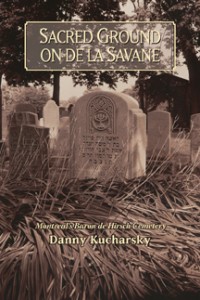

Danny is the author of Sacred Ground on de la Savane: Montreal’s Baron de Hirsch Cemetery, now in its second printing.

He also does a wide variety of corporate communications work, everything from writing news releases and brochures, to editing newsletters and creating online content. He was the Montreal correspondent for Marketing Magazine for several years.

He has won three gold Canadian Business Press awards for his writing and is listed in Canadian Who’s Who (University of Toronto Press).

Sacred Ground on de La Savane: Montreal’s Baron de Hirsch Cemetery

Book Description

Sacred Excerpt

Stones on tombstones at the Baron de Hirsch—and at any Jewish cemetery, for that matter (although it is not customary among ultra-Orthodox Jews)—are a familiar sight. It is not uncommon to see people at the Cemetery looking as if they’re digging for gold, but actually engaged in serious hunts for pebbles, so that they can put stones on loved ones’ graves.

So why do people place pebbles on tombstones? The answers are many as to how the custom originated.

According to Rabbi Maurice Lamm in The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning, it “probably serves as a reminder of the family’s presence.” The stones are a sign of respect for the deceased and act as evidence that the grave is visited and cared for.

The custom may hearken to biblical days when the monument was a heap of stones. The stones were often dispersed by weather or vandals, so visitors would place additional stones to assure the grave remained marked.

Others say it could be the end result of the custom of writing notes to the deceased and pushing them into crevices in the headstone in the way notes are pushed into the Western Wall in Jerusalem. When no crevice could be found, the note was weighted down with a stone. Eventually the paper would blow away or disintegrate leaving only the stone. That led people to think it was the leaving of a stone that was the custom.

Some believe the practice has superstitious origins and is akin to leaving a calling card for the dead. In the mythology of Eastern European Jewry, souls could take on a certain terror in death and return for whatever reason to the world of the living. The “barrier” on the grave was to ensure that souls remain where they belong.

In ancient times, shepherds needed a system to keep track of their changing numbers of flocks that went out to pasture. Since memory was an unreliable way of keeping tabs on them, the shepherd would carry a sling over his shoulder, and keep inside it the number of pebbles that corresponded to the number in his flock. That way he could always have an accurate daily count and verify that the same number returned at night.

The stones, therefore, may symbolize how precious each soul is to God, who, as it were, “counts” each person in the world. Although stones conjure a harsh image, they have a special character in Judaism. After all, the sacred shrine of Judaism, the wall of the second Temple, is considered “the foundation stone of the world,” while one name for God is “The Rock of Israel.”

Just as flowers that wilt may be a good metaphor for the brevity of life, stones serve as a good symbol of the permanence of memory. The pebble lets others know that someone did come and remember. Symbolically, it suggests the permanence of love and memory which are as strong and as enduring as a rock. Stones do not die, just as memories and souls are meant to endure.

Tribune Review

On sacred ground

Mike Cohen, The Jewish Tribune, May 29, 2008

MONTREAL – I must confess that I have never read a book before based on the anniversary of a cemetery. But Sacred Ground On De La Savane, published recently to mark the centennial of the Baron de Hirsch Cemetery in Montreal, contains such a wealth of information that just about anyone from the Jewish community – and probably the community at large – will have a hard time putting it down.

At the turn of the 20th century, more Jewish immigrants were arriving in Montreal than anywhere else on the continent, and the city’s small middle-class Jewish community suddenly had to meet the burial needs of many new, mostly poor, arrivals, who had little affiliation with the local congregations. Out of this crisis, the Baron de Hirsch Cemetery, one of Canada’s largest Jewish cemeteries, was established on an undeveloped expanse of swampland in the heart of the city.

The book, written by award-winning Jewish journalist Danny Kucharsky, traces the growth of the many burial societies that make up the cemetery and explains how the institution tackles issues all Jewish cemeteries must face: Security, burial rituals, modern management techniques and monument repair.

You’ll discover that the Baron de Hirsch Cemetery is the home for a wide variety of individuals who have shaped the city and its Jewish community. Mini-profiles highlight some of the site’s 60,000 residents including a Titanic victim, acclaimed poet A.M. Klein, a bagel maker, Yiddish Theatre of Montreal founder Dora Wasserman, gangster Harry Ship, a monument maker, and several politicians and artists.

Kucharsky was approached in 2005 to do the writing and research. Published by Véhicule Press, this is not the first book written about a cemetery in Montreal. There was a coffee table book called Respectable Burial: Montreal’s Mount Royal Cemetery, published by McGill-Queen’s University Press in 2003. A French book on the Catholic cemetery at Mount Royal (Notre Dame des Neiges) was published within the last two years. “There are some other books about cemeteries around the world, but surprisingly few, when you consider the increased public interest in them,” Kucharsky told me.

“Throughout its history, the Baron de Hirsch Cemetery has remained true to the philosophy that all Jews deserve dignity in burial,” Kucharsky said at the official launch for the book at Federation CJA headquarters. “The 1900 charter of the Baron de Hirsch Institute empowered the cemetery to ‘provide a burial ground for the interment of the dead poor.’ And that’s why this cemetery was founded in 1905, when room began to run out to bury the poor at the previous burial space – the Back River Cemetery, which is near the Sauvé Metro station. After several years of efforts, the current site was found in what was then known as Cote des Neiges West, conveniently located near a stop for the long-gone Park and Island Railway.

“To this day, the community continues to provide a respectable burial for those who cannot afford it, something that is quite unique in this city. In fact, there are no pauper fields at Baron de Hirsch: Indigent burials are scattered throughout the cemetery. There are no unmarked graves either. Instead of being buried in unmarked graves, people’s names live on [and] are indistinguishable from all others.”

As Kucharsky notes, the book also tells the tale of the large number of mutual benefit societies that comprise much of the cemetery. Among their services, these societies offered the sale of burial plots at affordable costs. Many of the societies have disappeared in recent decades – the Hebrew Sick Benefit Association for example – but the cemetery owes much of its existence to them, Kucharsky insists.

The book provides some little known facts such as the cemetery’s establishment of a perpetual care fund that ensures that graves are maintained even if there are no family members around to care for them. This fund has grown to levels that ensure the continued maintenance of the cemetery well into the future. “We have an obligation towards the dead in the Jewish community, and clearly, the Baron de Hirsch cemetery has met that obligation,” Kucharsky says.

There are, in fact, a lot of interesting side stories in the book such as the historical background of the different sections, the costs of burial then and now, fallen tombstones, problematic drivers within the cemetery grounds and acts of vandalism. In April 1990, 25 monuments were overturned and desecrated with antisemitic slogans. B’nai Brith Canada Executive Vice President Frank Dimant is quoted at that time as saying, “I am deeply saddened by this display of hate,” noting that his father and father-in-law are buried there.

Perhaps former cemetery president Jacques Berkowitz sums up the history best: “Cemetery is a very difficult thing to talk about. People hesitate. They don’t want to know about it. People don’t plan properly. Comes the time, they are so distraught.”

What is the future for the cemetery? Given the realities of supply and demand, space is slowly running out. Kucharsky concludes that the Jewish community will soon come full circle and be in the position it was more than 100 years ago – looking for a new burial ground for indigents and for the general community.

Sacred Ground On De La Savane is available in Montreal book stores and online, with more outlets to come.

Mike Cohen is the Tribune’s Quebec bureau chief. He can be reached at info@mikecohen.ca